Tipping Points Definition

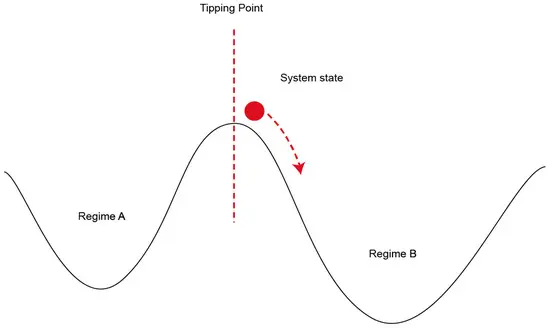

As defined in The Global Tipping Points Report 2023 (Lenton et al., 2023), tipping points are “critical threshold[s] beyond which a system reorganizes, often abruptly and/or irreversibly”. This definition captures three essential aspects: the nature and state of the system itself, the transition path that links different states, and the concept of thresholds that, once crossed, trigger systemic change.

A tipping point is reached when a system tips over from regime A to regime B (Rauter et al. 2019, Obligation or Innovation: Can the EU Floods Directive Be Seen as a Tipping Point Towards More Resilient Flood Risk Management? A Case Study from Vorarlberg, Austria)

State of systems

Human systems are composed of deeply interconnected political, economic, technological, and social-behavioural domains. Together, these domains define the state of a system, which may exist in a relatively stable equilibrium or pass through a period of instability during which it transitions toward a new state. A tipping point refers to the conditions under which a system shifts from one stable state into an unstable transitional phase, setting in motion the reorganisation that leads to a new equilibrium. The forces that push the system toward this shift—whether endogenous or exogenous, intentional or unintended, arising from collective action or individual agency—are important, but it is ultimately the system that tips, not the conditions themselves.

Consider our current global configuration as an example: democratic governance, a linear economic model, early-stage artificial intelligence, and a social order centred more on individualism than on community. This represents a stable yet unsustainable state. A political decision to internalise environmental costs into prices could change the incentives faced by producers, encouraging them to adopt circular economic models, invest in sustainable technologies, and offer more affordable environmentally friendly products. In this scenario, the policy decision acts as a shock that enables the system to cross a critical threshold, triggering a transition from its original state into an unstable phase and eventually stabilising in a new, more sustainable configuration.

Sometimes, however, a single condition is insufficient to induce systemic change. Additional thresholds may need to be reached before the system tips. For example, a technological breakthrough such as commercially viable nuclear fusion could provide abundant low-cost energy, complementing the policy change and reinforcing the transition. In this case, both the political decision and the technological innovation together form the tipping point conditions necessary for the system to reorganise and settle into a new equilibrium.

Three types of tipping point. Schematic representations of: (left) bifurcation-induced tipping; (middle) noise-induced tipping, and; (right) rate-induced tipping (Lenton, et al., 2023, The Global Tipping Points Report 2023).

Transition path

As systems evolve from one stable state to another, they pass through an unstable phase during which the relationships and structures within their domains are reorganised. However, the presence of change does not guarantee that the system will successfully reach a new equilibrium. Transformations can stall or fail if the necessary conditions are not fully met, causing the system to revert to its original state. In other words, crossing certain thresholds may set a transition in motion, but without sufficient momentum, the change may be temporary or incomplete.

Revisiting the earlier example, political reform and technological innovation might trigger a period of reorganisation. Yet if public support is lacking, the transition could lose momentum and collapse. Because the political, economic, technological, and social domains are highly interdependent, they can amplify change through positive feedback loops but can also resist transformation through institutional inertia or cultural resistance. If all necessary conditions are not fulfilled, the system may retreat to its initial configuration rather than consolidating a new one.

Conceptual framework for positive tipping points in human systems (Smith, et al., Working Paper, Criticality and critical agency in societal tipping processes towards sustainability).

Thresholds

Systemic transformation depends on the crossing of one or several critical conditions that define a tipping point. These thresholds may be conceptual, such as the minimum speed at which information must diffuse through a network or the level of material durability required for effective reuse. They can also be associated with broader phenomena, such as widespread recognition of human equality or the emergence of new communication platforms like social media.

Scholars continue to debate whether tipping points involve a single decisive threshold or a sequence of multiple conditions along the transition path. Evidence of early and late failures in attempted transformations suggests that multiple thresholds often exist, from the initial divergence from the old equilibrium to the consolidation of a new one. Identifying these thresholds is essential for assessing a system’s tipping potential and for designing strategies that can initiate and guide sustainable transformations.

Summary flow diagram of overall methodology (noting that in practice it is more iterative than this linear depiction suggests) (Lenton et al. 2025, A method to identify positive tipping points to accelerate low-carbon transitions and actions to trigger them)

Example – The Historical Development of the German Bottle Reuse System

For much of the twentieth century, Germany’s beverage industry relied on bottle reuse out of necessity. Materials were scarce, and discarding packaging was not an option. However, the system was inefficient and fragmented, as each company managed its own bottles. A major shift occurred in 1969 when the Genossenschaft Deutscher Brunnen cooperative introduced a standardised reusable glass bottle. This innovation reduced costs, enabled large-scale logistics, and made reuse more attractive to producers and consumers. Standardisation acted as a critical threshold, and as more companies joined the cooperative, the system became more efficient, creating a reinforcing feedback loop. Over time, reuse became not just practical but also a social norm. For decades, more than 80 percent of mineral water was sold in reusable bottles, and the system appeared locked into a sustainable equilibrium.

Yet systems that tip positively can also tip negatively. By the 1980s, new pressures emerged. Consumers began to prioritise convenience over environmental considerations, retailers were reluctant to invest in refillable infrastructure, and single-use plastic bottles became lighter, cheaper, and more customisable. Policy interventions sometimes exacerbated the problem. A mandatory deposit on single-use bottles, intended to discourage their spread, made recycling more convenient than returning refillables. Confusing parallel systems further undermined public engagement. The feedback mechanisms that had once supported reuse now worked against it. As these forces accumulated, the system crossed another threshold: the economic logic, social norms, and institutional structures that had supported reuse collapsed, and single-use packaging rapidly became dominant.

The rise and decline of Germany’s bottle reuse system illustrates how systemic transitions depend on the crossing of key thresholds—moments when small changes unleash large-scale shifts. Standardisation, collaboration, and public acceptance once propelled the system toward a self-sustaining circular model. Later, convenience, cost advantages, and shifting market dynamics pushed it toward a new equilibrium centred on disposability. This example underscores a broader lesson: sustainability transitions are not solely driven by technology or policy. They depend on timing, alignment across domains, and the balance of feedback dynamics that can steer a system either toward a regenerative future or back into a linear past.

Illustrative visualisation of the development of bottle waste management systems in Germany from regional reuse to awidespread reuse system to a single-use system, and potential future pathways. The valleys represent alternative stable states ofthe system, which are evolving over time. The bottle represents the actual state of the system at a particular time. The dashed lineshows the historical trajectory of the system and the dashed arrows the possible trajectories unfolding now and into the future. (Ong, et al., Working Paper, Tipping dynamics in packaging systems: How a bottle reuse system was established and then undone)